A Parent's Guide to Eating Disorders: Recognition and Support

A gentle guide for parents during Eating Disorder Awareness Week. Learn how to spot early signs, foster healthy conversations about food, and support your child’s mental wellbeing with practical, empathetic advice

Eating disorders are serious mental health conditions with biological roots and psychological complexity. For parents, the challenge is often distinguishing between "fussy eating" and a developing illness. With the average gap between the onset of an eating disorder and the start of treatment standing at three and a half years, early recognition within the family is the most powerful tool for improving a child's long-term outcome.

For Eating Disorders Awareness Week 2026 (23 February to 1 March), the theme of Community starts at home. Parents are the primary observers of a child's behaviour and the first link in the chain of support.

Moving Beyond the Stereotype

It is common for parents to believe that eating disorders only affect teenage girls from specific backgrounds. However, modern data proves that these illnesses do not discriminate:

- Gender: Roughly 25% of all eating disorder diagnoses in the UK are in males, with higher representation in specific disorders like binge eating disorder (approximately 40%).

- Age: While often framed as adolescent conditions, they can develop at any age.

- Background: Research shows that children from Black, Asian, and minority ethnic communities are often underdiagnosed due to persistent clinical biases.

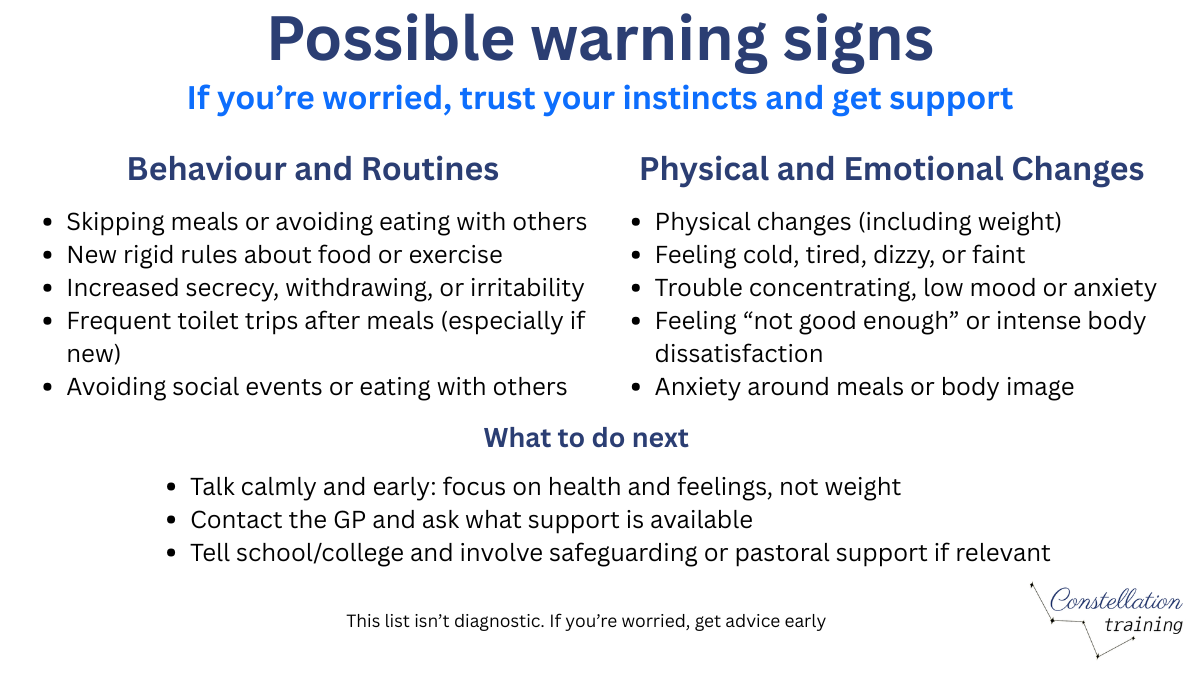

Recognising the Signs in Children and Young People

Eating disorders are frequently characterized by secrecy and shame, meaning children rarely disclose their struggles voluntarily. Parents should look for shifts in behaviour, mood, and physical health.

Changes in Behaviour

- Social Eating: Avoiding family meals or making excuses to eat alone in their room.

- Strict Rules: Developing sudden, rigid dietary rules or an escalating preoccupation with calories and "clean" eating.

- Rituals: Cutting food into tiny pieces, rearranging food on the plate, or eating in a specific, fixed order.

- Exercise: An obsessive need to exercise that continues even if the child is injured, ill, or the weather is poor.

Emotional and Physical Indicators

- Mood Swings: Heightened anxiety or irritability, particularly around mealtimes.

- Body Checking: Frequent checking of their body in mirrors or, conversely, a complete avoidance of mirrors.

- Physical Markers: Feeling constantly cold, thinning hair, or dental erosion from repeated vomiting.

Important: Weight is not a proxy for illness severity. A child can be at a medically "normal" weight while experiencing severe physical and psychological harm.

Why They Develop: It Is Not Your Fault

Families do not cause eating disorders. This is one of the most important things for parents to understand. While certain family dynamics can influence risk, blaming yourself or your child is neither accurate nor helpful.

The risk is "biopsychosocial": a combination of genetic vulnerability (accounting for at least 50% of the risk), psychological traits like perfectionism, and environmental pressures.

Taking Action: The First Steps

If you suspect your child is struggling, how you approach the conversation matters.

- Preparation: Choose a quiet, private time when no one is rushed.

- Focus on Feelings: Avoid commenting on their weight or appearance, as this can trigger a defensive response. Instead, mention behaviours you have noticed (e.g., "I've noticed you seem very stressed during dinner lately").

- Listen: Allow your child to speak without interruption or judgment. Avoid the urge to "fix" the problem immediately or offer reassurance about their weight.

- Seek Professional Help: The goal of your support is to bridge them to clinical care.

Navigating the Healthcare System

While adult services in the UK face significant delays, there are specific standards for children:

- NHS Waiting Time Targets: The NHS aims for 95% of urgent referrals for under-18s to be seen within one week and routine referrals within four weeks. However, these targets are not consistently being met: recent data shows approximately 64% of urgent cases and 79% of routine cases starting within target timeframes.

- FREED: This is an early intervention pathway specifically for young people aged 16 to 25 experiencing their first episode of an eating disorder (not applicable if the young person has been unwell for an extended period).

Support Resources

- Beat Youthline: 0808 801 0711 (for under-18s)

- Beat (General): beateatingdisorders.org.uk (online resources, adult helpline 0808 801 0677)

- Student Minds: studentminds.org.uk (mental health support for students)

Supporting Recovery at Home

If your child enters treatment, knowing how to support recovery at home is essential. Well-meaning actions can sometimes inadvertently make things worse:

- Avoid food policing: Monitoring every bite, commenting on portion sizes, or expressing approval/disapproval about what your child eats creates anxiety and reinforces the disorder.

- Create low-stress mealtimes: Keep conversation light and unrelated to food. Do not force eye contact or insist the child eat with the family if this causes distress during early recovery.

- Do not comment on weight or appearance: Saying "you look healthier" or "you've gained weight" (even positively) is unhelpful. Focus on how your child is feeling, not how they look.

- Let clinicians lead: Follow the guidance given by your child's treatment team. If you are uncertain about what to do, ask them directly rather than improvising.

School and Educational Settings

School staff are often among the first to notice signs of an eating disorder, particularly through peer comparisons, avoidance of communal eating, or changes in PE participation. Whether and how to involve school depends on your child's age and circumstances:

- Safeguarding duties: Schools have a safeguarding responsibility. If your child is at medical risk or their attendance is affected, the school will likely need to be informed.

- Practical adjustments: Schools can make adjustments including allowing your child to eat lunch in a quieter space, modifying PE requirements, or providing exam accommodations if concentration is affected.

- Coordinating care: Your child's treatment team, school, and family should ideally work together. Schools may have a designated mental health lead or SENCO (Special Educational Needs Coordinator) who can coordinate support.

While this guide is a starting point for gentle home conversations, we understand that some situations require a deeper look at the underlying complexities. If you feel you need more technical detail on the clinical signs or professional support pathways, you can explore our In-Depth Guide to Eating Disorder Awareness. This resource provides the practical, detailed information often needed when navigating more challenging circumstances.

Constellation Training provides accredited Mental Health First Aid training to help adults support the young people in their lives.